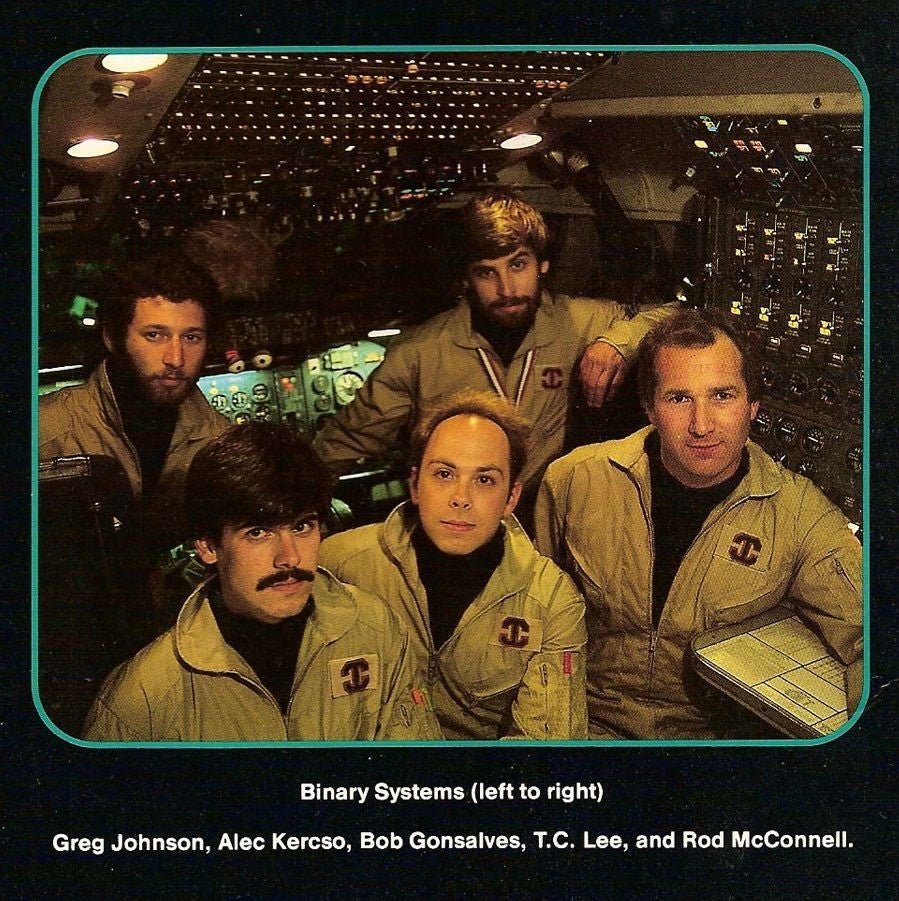

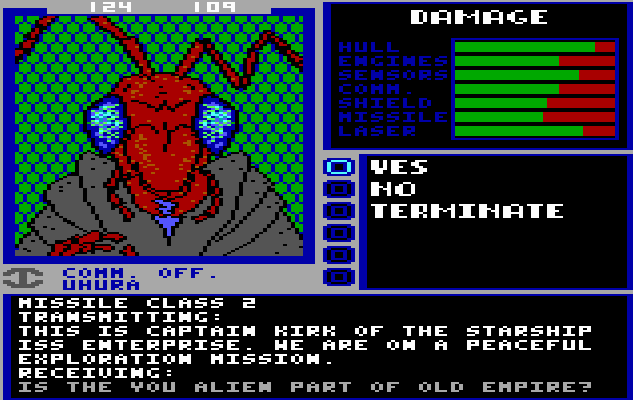

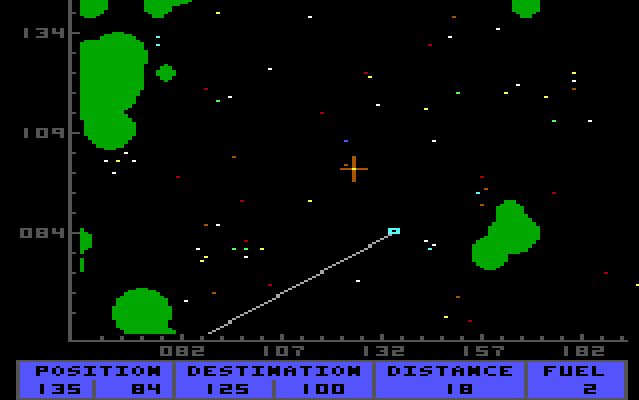

Towards the end of 1982, McConnell formed a company, Ambient Designs, to work on the concept - known as Starquest at this point - with the blessing of the embryonic publisher. One of his first employees was programmer Alec Kercso. “I was in my senior year at UC San Diego when I met Rod,” says Kercso. “At the time most people, and certainly most students, didn’t have a personal computer at their desk and compared to today there wasn’t nearly the number of games out there.” While finishing up his degree in linguistics, Kercso fondly recalls playing classic adventures such as Rogue and Zork, enjoying the exploration and puzzle solving aspects they both presented. In February 1983 he interviewed for a programming role with McConnell, returning to university with a job and a book on the programming language, Forth. He also purchased an Atari 800 - the home computer that Starflight was intended for. Also studying linguistics (actually a sub-division known as bio-linguistics), and rooming with Kercso at college, was Greg Johnson. Curious about the exciting project that his friend had become involved in, Johnson’s interest in Starflight led to him making some early key contributions. “When I came onto the project I was very enthusiastic about creating a whole universe, a deep story and alien races with personalities while putting the player into a big adventure. I managed to convince them, and the project changed direction.” he explains. One of the most memorable facets of Starflight, its overarching story, complete with an extraordinary twist, had been set in motion. Beginning in a circular star base that instantly betrays Starflight’s main inspiration, TV series Star Trek, the player first assembles their team and assigns training to each crew member in the familiar roles of science officer, navigator and so on. Following this, it’s time to pimp up your spaceship before beaming aboard and setting off to the stars. There’s a catastrophic event brewing: stars throughout the galaxy are flaring up, destroying any planet within their fiery reach. The crew’s ultimate goal is to discover what’s causing these occurrences in order to prevent the same happening to their home planet of Arth. Throughout the galaxy roam many alien craft, each with its own personality and demands, and the quest for endurium (Starflight’s equivalent of Star Trek’s dilithium crystals) drives the need to explore new worlds and extract their valuable minerals. “For all of us, it was our first videogame, and we pretty much made it all up as went along,” reveals Johnson. “Star Trek was definitely the biggest influence, and maybe to some extent Dungeons & Dragons in general.” Interestingly, Johnson was mentored in his student days by Paul Reiche, who would go on to design the first two Star Control games along with Fred Ford. In a neat development cycle, Reiche used his experience helping Johnson and his colleagues with Starflight to design his own series of which the Binary Systems game is often cited as an influence, before Johnson lent his own experience on Starflight to his friend and Star Control. By the end of 1983, the Starflight team had expanded to include designer/programmers Bob Gonsalves and Tim Lee, joining Kercso, McConnell, Yarborough, Johnson and an experienced engineer called Dave Boulton. It was a large team for a videogame of the time - although unsurprising considering what they were looking to create. “That was part of the original concept,” explains Kercso. “We wanted to create a game the likes of which had no-one had seen before. It wasn’t going to be just a single game, but an entire universe.” The idea was staggering, and it was soon apparent the Atari 800 would not be up to the job. “Maybe nine to ten months in, we made the decision that [the Atari 800] wasn’t going to be viable,” continues Kercso. “So we changed platforms to the Commodore 64… for all of one month.” Tim Lee, a veteran PC coder, suggested that they switch to that platform, instigating Starflight’s third, and final development cycle. Now ensconced on its ideal platform, development on Starflight began in earnest. Given the new ground that was being explored, customization was high. “We started with a version of Forth called valForth,” says Kercso. “But contracted with Glen Tenney who created a custom version of the Forth platform, specifically for Starflight.” Meanwhile, Tim Lee wrote the graphics routines - at the time, amazingly fast - while Kercso and his fellow coders tried to pull it all together. “Remember, it was the early 80s; there weren’t libraries of code we could download to drop into the game. Everything was custom.” The scope for Starflight was incredible. “Sometimes ignorance is a blessing,” grins Johnson. “If we had really been aware of what we were trying to do, we probably wouldn’t have attempted it.” Dave Boulton, feeling that they were becoming too ambitious, left the team. Continues Johnson, “I loved Dave and was very sad to see him go. He was such a nice and super smart guy - I can’t remember exactly why he left, but I do know he had his concerns.” Boulton’s fears were understandable. Starflight was growing, and becoming problematic. “That was probably the biggest issue with the game,” explains Kercso. “As we worked on it, we thought of a few new things we could add and new plot lines. Its development was as much of an experience of discovery as the gameplay of the final game.” One of the most important technical aspects of Starflight was the Fractal Planet Generator, Dave Boulton’s hypothesis for creating the game’s huge galaxy that was revamped and implemented by Tim Lee, as Johnson explains. “Tim came up with the idea of using fractals and a seed number to generate an entire galaxy, right down to the terrain and individual lifeforms of every single planet. The key was that the information was stored in the algorithm and rules for generation and not the data. In other words, it would be generated the same every time and there was virtually no limit to the size - all you needed was the right rule set.” For a linguistics student such as Johnson, the interaction between the player and alien species was a highlight of development. “We had AI for combat and AI for conversation,” he remembers. “But the really fun and interesting bit was the conversation and relationship AI.” Using a system that’s still remarkable, even by today’s standards, the aliens’ reaction to the player depended on multiple levels of postures and dialogue. “Every alien race had what we called Emotional Disposition Levels - or EDLs - and things you could do, like raise shields, arm weapons and the races on board your ship would drive that up or down.” The EDL had a short-term reaction that would change rapidly and a long-term factor that changed more slowly. With each race holding different thresholds within the scale, the result was a complex system that meant the player had to be very careful and considered during alien encounters. “It was an awesome system. I designed it, but all of the engineers on the team helped think it through and make it workable. We worked really well together.” Each member of the close-knit team provided a fundamental part of Starflight. “We haven’t even talked about Bob Gonsalves involvement yet,” notes Kercso. Originally on board to help with the Atari 800 version, when the game moved to PC, Gonsalves programmed the entire terrain vehicle on-planet experience. “He was another experienced programmer, and I learned a lot from him. As he gained a reputation for solving pernicious bugs, we gave him a nickname; Bob Gonsalves became ‘Bob Can Solve This’.” Additionally, the team infused the game with their own quirks and ideas. Kercso himself created the impatient toe-tap of the starport spaceman avatar, while everybody added their own personal artifact that could be found on a random planet. “My own was the ‘red herring’, a very valuable object that was 0.1 cubic metres larger than the maximum capacity of the terrain vehicle!” he adds impishly. Development on Starflight was unusually long. The Electronic Arts contract was signed at the end of 1982; development began in 1983, and with the change of formats and ambition elongating matters, by 1985 it was still going, by which time Sierra On-line had almost released the first in its Space Quest games, causing the name change from Starquest to Starflight. Around the same time, Ambient Designs became Binary Systems, but irrespective of name changes, the game would never have stood a chance without its dedicated publisher support. “Necessary re-designs and major technical hurdles slowed the project and cast a lot of doubt whether it would ever be completed,” recalls Kercso, and Rod McConnell’s passion for the game played a vital role. “Rod did an amazing job of convincing Joe [Ybarra, Starflight’s manager at EA], and in turn Joe of convincing EA senior management that we would not only get the job done, but that the end result would be worth it.” In the end, it’s hard to imagine the suits at the fledgling publisher disappointed. Binary Systems had produced a truly ground-breaking title that had found its natural home on PC. “Bing Gordon, one of the original founders of EA told us that he stopped sleeping for a few nights as he got sucked into the game,” smiles Johnson. “We got lots of positive feedback, and we were just exhausted and excited to finally get the game out into the world.” Over one million copies sold later, and despite the monumental effort, it was all worth it. Coming on two 360 KB floppy disks, simply squeezing Starflight’s massive universe onto those two floppies was an achievement to be proud of. User approval was high, too. Gamers, like EA’s Bing Gordon, took to the open-galaxy gameplay, investing themselves mind and body into their own bespoke world of exploration and discovery. That investment would spectacularly pay off in the conclusion to the game’s main story, and the plot twist that suddenly left the brave explorer questioning their own morality and actions. The source of the solar flares is a Crystal Planet, wandering around the galaxy and causing the stars to destroy all life in their respective systems. After discovering remnants of the Old Empire on Earth, the player is eventually led to the Crystal Planet, and makes a startling discovery: the endurium that they’ve been using to burn their way around the galaxy is actually a living, sentient being. “I have always disliked stories where the bad guys are simply evil,” notes Johnson. “In fact, it was quite an ‘aha!’ moment when I came up with the idea that the player themselves would be the aggressor. It was really intended to make the player need to think a bit - isn’t that the point of all good science fiction?” Like Mass Effect 20 odd years later, decisions have consequences, and there’s always something out there, waiting to be discovered. Starflight’s success meant a sequel was quickly put into development, with Commodore 64, Amiga, Atari ST and Sega Mega Drive ports of the first game all appearing over time. For those involved, it remains a life-changing experience. “I still count Starflight as one of my most significant works,” tells Kercso. “I mean, here we are, 35 years later and not only am I doing this interview, but I still get occasional fan mail. When someone tells you how much they loved Starflight and that’s why they studied computer science and became a software engineer, well that’s a fantastic feeling.” Like Kercso, Johnson still receives fan mail from time to time as he also continues to try and bring new Starflight adventures into reality. “We almost succeeded with a crowdfunding campaign a few years back and right now there are some people working on an anthology of short stories set in the Starflight universe.” Since Starflight, Johnson has scored further successes, most notably with the ToeJam & Earl games and continues to work in the industry, 35 years after the release of his first game. “Yeah, I am still chugging away as a starving indie developer, and remain super proud of the work we did. It was an amazing team, and Starflight was my first game, and like your first date or kiss, it’s something that has a very special place and meaning.” Thanks to Alec Kercso and Greg Johnson for their time. Adapted versions of both Starflight and Starflight 2 are available to buy on www.gog.com.