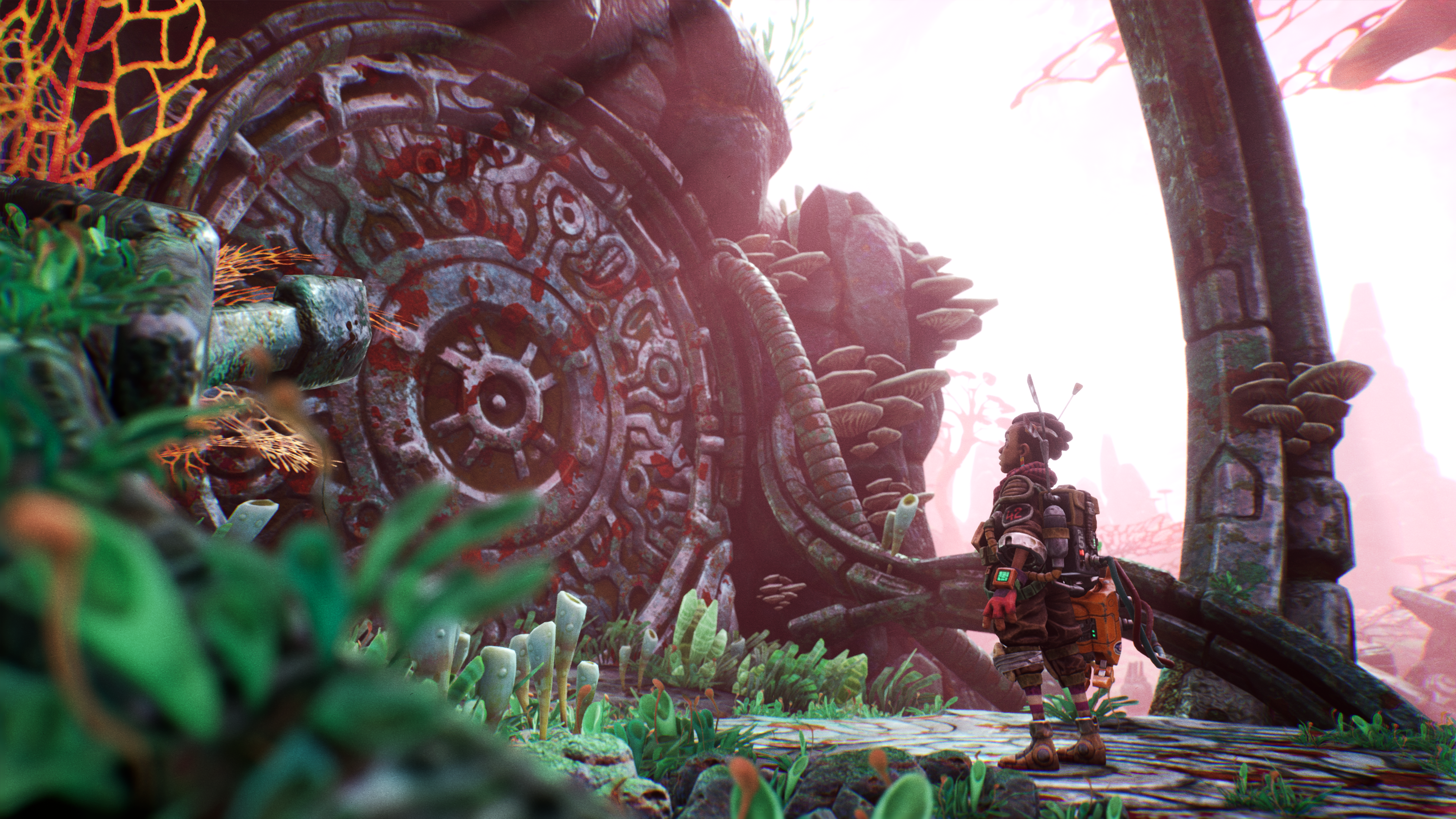

This is the latest release from the team that made the glorious SteamWorld adventures, and despite the shift to 3D, it shares qualities with those games - a certain brightness, a love of layering on the detailing, and a pleasingly compact nature. Everything here is fun, and everything is interesting and clever. Once you’re through with the fun, interesting, clever stuff, the game is over. The Gunk is a treat. And the gunk is a treat. The game casts you as one of a duo of space haulers. I think that’s the idea anyway: these two jet around the galaxy trying to find anything they can turn into energy and sell. As the game begins they land on a beautiful planet filled with weird, colourful wildlife and the promise of riches. Oh yes, and the gunk. The gunk is black and grey and brown and deep, bloody red. Ribena from Hades! It bubbles and throbs and gets everywhere. It clogs the game’s beautifully chunky levels. At times, it moves through the air like the murmuration of some hideously infested starlings. Reader: I love the gunk. Just to see it is to know how bad it is, and to know what you want to do with it. You want to clean it up. And in The Gunk you can. Your standard tool in The Gunk is a vacuum cleaner thing with apparently limitless storage. It sucks up the gunk like nothing else. It spirits it down! It is a delight to rove around the world, a stocky little human covered in hand-made gadgets, and just chug through the gunk whenever you find it. The vacuum also has uses once the gunk starts turning up with enemies: you can suck them in and then spit out the horrible bouncing toothed basketballs that appear early on. As for the rooted spitters, you can suck in their heads and then pull them out of the ground. Bigger enemies turn up - not many, because it’s not really a combat game - and they all suffer the same vacuumed fate in the end. It’s a joy. Once you’ve freed a section of the world from gunk, colour and life returns. The grey fades and foliage bursts out of the ground with rubbery leaves and strange characterful fronds. New paths open up - there’s a bit of friendly low-stakes platforming to be had in The Gunk as you make your way through the world - and certain kinds of plants offer resources or items used in puzzles. The resources tie into some fairly simple upgrades, but the plant-powered puzzles are frequently a treat. This isn’t a hard game, instead it’s one in which most activities have a lovely zip to them. You might climb higher by finding the right kind of seed to chuck into a glowing pool, so that it sprouts huge bouncy platforms for you to use. Wreckage blocking your way might require a different kind of seed that explodes seconds after it’s been plucked. Onwards! A satisfying loop quickly emerges. As the story progresses and your reasons for staying on this planet start to move away from simply scavenging for resources, you find yourself clearing areas of gunk and then exploring, opening up new areas which must also be cleared of gunk. It’s so satisfying to clear the stuff up I’d probably do it even if the map wasn’t constantly unfolding, the fast-travel spots weren’t announcing themselves, and the puzzles weren’t getting more complex. That’s not bad, is it? There is more to The Gunk - loving details, like the chunky Game Boy the protagonist has clipped to her suit, or the relationship between the main characters that emerges and evolves as you explore, a beautifully observed study of old friends struggling with new challenges, a spacey form of the gig economy, and the pressures of their personal conceptions of one another that have maybe ossified into caricature. It’s elegantly done, and I think it’s a teeny bit of a shame that a few swears intrude in what is otherwise a perfect game for children. I must have reached that age, I guess, but I also think there’s also a question of harmony: in a game so deftly constructed, the swearing just doesn’t fit. As the journey shifts and becomes a bit darker, there’s a real flash of steel at the core of it all. If you’ve played the SteamWorld games, you’d probably expect this, but it’s still a delight to see a game like this built with such craft and obvious humanity. I started The Gunk worrying about how one of the great 2D design teams would cope with three dimensions. The truth is they cope so effortlessly that I just spent the next four or five hours gloriously lost in what they had built.