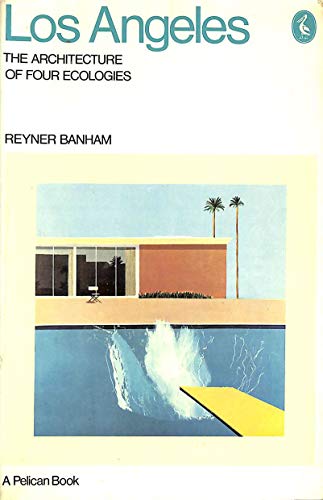

I’m reading Banham again because his generous and perceptive take on LA always feels like comfort reading. In March 2021, just opening the book seems to bring the warmed-concrete spaciousness of that city, with its standing freeway pillars and playful flow between urban and wilderness, into the saggy darkness of the lockdown home. And I’m looking through old mags because Banham sent me back to GTA 5 and then GTA 5 sent me back to a Wipeout Fusion print ad, a double-page spread, once seen and never forgotten, in which London has been chosen as a site for the development of a multi-gajillion pound anti-grav racing track, and the citizens are not happy about it. STOP THIS TRACK BEING BUILT, says the rubber-stamp lettering in the top-left corner. (That lettering, like the Tax-Payer’s Alliance tone of the copy is just perfect.) At the bottom of the ad, we learn about how the track will affect London in terms of pollution and safety. But the bulk of the double-page is taken up with a rendering. Here is the Thames with this astonishing racing track ribboned around it, looping through Tower Bridge and banking over the Tower itself. Two worlds intermingled. The horror and the beauty of it. Nobody would ever attempt such a thing, right? But if they did… I wish GTA 5 handled like Wipeout. I wish it had the magnesium burn of those sci-fi exhausts. I wish it had its thrumming futuristic zip and that sort of ghostly connection to the road, so fishy and elastic on corners, so strangely grippy on straights you can almost sense the radioactive connection buzzing between vessel and surface, that single record-stylus point on which the whole thing pivots. But venturing into the weird Craigslist world of GTA Online has revealed that this game does at least have tracks that are worthy of Wipeout - vast city-spanning things delivered most often in terrifying lengths of striped Beetlejuice piping, tracks laid upon a city but rarely connecting with it, a deeply self-involved transit system for speedheads and will-‘o-the-wisps - a spook country. Stop this track being built, etc. And so I love GTA Online’s races, and not for the races themselves, even though they can become pretty intricate and demanding, the best of them forcing you to switch vehicles on the fly, turning into a jet just as the track runs out, and switching back to a car to nail a terrifying drop onto a ramp the size of Nebraska. I love them because they are so weird and subversive. GTA 5 has spent more effort than any game I can think of looking hard at a real place - Reyner Banham’s favourite city - and, aside from a few weak puns, thinking about how to bring its textures and gaps and absolute material reality into the digital space of an open-world sandbox. Los Santos genuinely feels worn and travelled. It makes sense, right down to the movements of the virtual fire department. It even has the correct LA light, that flat brightness that brings the best out of stucco and glass. And then Online allows for these looping, arcing race tracks that simply cannot be made sense of. It’s surrealism built on realism. It’s weird to think that it’s only because of an accident that I discovered any of this. If I hadn’t stumbled on the racing options, I would never have known these tracks were around and about us, built onto the city, but separated by some kind of ludic dimensional barrier. And suddenly it all makes sense: I love the gleefulness of these tracks, which means I love that this game that cares so deeply about a form of realism is suddenly letting go. And in letting go, the canvas for its imagination is the very city that it stared at so long and so carefully in order to recreate in the first place. Here, as Dorothy Parker might have put it, here is the disciplined eye and the wild mind that is present in almost all games in some way - but now we get both and the point at which they clash! What happens when they clash? The best tracks, my favourites, are not marked so much by what they do - what kind of looping stunts they employ - but how keenly they glance against the city that they can barely bring themselves to acknowledge. Unless you’re willing to nick a chopper, Los Santos is home to a lot of fairly useless height: the skyscrapers are all there, but you never get to see the best bits. In the races, though, you do - you steer past the top of the US Bank Tower, with that sunbeam crown that got such a vibrant airing before being blown to pieces in Independence Day, and then past the Fox building, also known by its true name of Nakatomi Plaza. The bleached Sepulcher of City Hall suddenly seems very small - you have to dip down to rush past this building which, in its own way, once scraped the sky too. These are places that open-world games often have to include but can struggle to make use of, just as your imagination of the real Los Angeles may include those lovely smooth drone shots of helipads and whatnot, but the reality of your trip there is mainly freeways and Shake Shacks. (Not to knock either.) Weirdly, the tracks also do something to the scope of GTA 5’s island. The upper storeys are suddenly in reach, but an entirely different mode of auto travel - lots of long, long straight lines and wide curves - lays a different map on the place, and reveals the inherent closeness of everything in the game. This is where GTA 5 diverges from the real Los Angeles, which is every bit as vast as it seems (and the land as ancient). In the main campaign, navigating the mean streets, you can fall for the simulated sprawl. Up here, though, with the air all around you and point B visible even as you rocket out of point A, you start to understand the tricks that have been employed to compact everything. Ultimately, the online tracks are so pleasing, I think, because of the things like this that they accidentally reveal, and also because they hinge on this interaction between the fantastical and the mundane that can frequently define the real city. 7-11s and Circle-Ks abound, and yet a man once dreamt of building a museum in Griffith Park that would contain a full-scale replica of the Parthenon inside its main gallery. One of its best buildings was inspired by a newbie architect and a literal dream. Its water and power HQ is an airy modern pagoda set amongst ponds. The final kink is that the fantasy architecture of the tracks is delivered with the sort of sun-damaged utility that the game employs to add a patina of age and history and realism elsewhere. The tracks are deeply physical objects, with buttresses and pillars holding them up, and their material is scuffed and their colours seem somewhat faded - they are of a part with what Banham memorably refers to as “the monuments of the freeway system.” In truth they put me in mind of the pleasantly foot-travelled texture of a soft play: better days have come and gone, but a certain ragged brightness remains. Re-reading Banham this last week I’ve finally understood something that, to my shame, he makes deeply explicit in the text. Los Angeles is no more a city built on freeways than New York or Barcelona or Tokyo or Capetown. Rather, “the less densely built-up urban structure of the Los Angeles basin has permitted more conspicuous adaptations to be made for motor transport than would be possible elsewhere without wrecking the city.” He continues: “Los Angeles has no urban form at all in the commonly accepted sense,” which certainly rings true for a lot of my friends who go there the first time and find it shapeless and ever-spreading, a consuming flatness that refuses to lodge meaningfully in the mind and coalesce into places and directions and chunks of urban sense. It has no urban form, perhaps, but jeepers it has themes, and a unique idea of itself that lives in the minds of people who love it and hate it and want more of it. An idea that can be rendered using realism or surrealism - or at best, both.