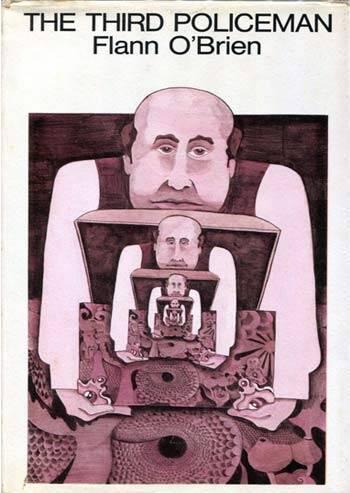

Meet ‘Flann O’Brien’: inspiration for the greatest deconstructionist, science-fiction, comedy game no-one’s made yet. Brian Ó Nualláin [Brian O’Nolan] - alias ‘Flann O’Brien’, alias ‘Myles na gCopaleen’ [Myles of the little horses], alias ‘Brother Barnabas’, alias ‘Count O’Blather’, alias ‘George Knowall’, alias ‘Lir O’Connor’, alias ‘Velvet Texture’ (my personal favourite) - was born in 1911 to an Irish-speaking family in Strabane, County Tyrone, in what is now Northern Ireland. Educated at University College, Dublin, where he became a prominent (and provocative) member of the intellectual scene, he wrote prolifically in both Irish and English, evolving a form of post-modern meta-fiction in which gangsters and cowboys rub shoulders with Irish mythic heroes, good novels have not one beginning, but three, and characters rise up to put their author on trial for the many indignities to which he has subjected them. These early experiments eventually crystalised in O’Nolan’s first great anti-novel, At Swim-Two-Birds (1939), a genre-bending deconstruction of Irish literary history and a raucous satire of the Dublin literary scene which won praise from Graham Greene, whose glowing reader’s report helped to get the novel published, Dylan Thomas, who described it as ‘just the book to give your sister - if she’s a loud, dirty, boozy girl’, and O’Nolan’s hero, James Joyce, who detected in O’Nolan’s writing the ’true comic spirit’. Undeterred by the poor sales and lukewarm critical reception which greeted At Swim-Two-Birds, O’Nolan set about writing what is widely regarded as his masterpiece, The Third Policeman. Composed in the closing months of 1939 and the early months of 1940, the novel tells… a story that is frankly impossible to summarise in a succinct or satisfactory manner, let alone one that does justice to its darkly hilarious tone, surreal imagination, and unique blend of philosophical profundity and profound silliness. So, instead of attempting to offer a comprehensive account of the ‘plot’ of The Third Policeman, I will simply offer a list of some of the things it features:

An international secret order of one-legged men. A TARDIS-like police station that appears to be both two-dimensional and three-dimensional at the same time, with no perceptible ‘sides’, and a ‘back’ and ‘front’ that may be seen simultaneously. A room within this police station whose cracked ceiling comprises a map which shows ’the path to eternity’. A second, deeper ’eternity’ contained within the ’eternity’ to which this map leads, in which time is at a complete stand-still and any object may be conjured into existence in any quantity, but from which no matter can ever be removed. A reality-warping substance called ‘Omnium’ which simultaneously behaves like a wave and a particle and constitutes ’the essential inherent interior essence which is hidden inside the root of the kernel of everything’. A policeman who can flatten light into sound using a mangle, and who has manufactured a series of ornate boxes, each concealing a smaller version of itself, stretching on beyond the limits of human perception to apparent infinity. Numerous footnotes from a critical study of the life and works of a fictional philosopher and inventor called De Selby, who proposed that all humans should be clad in ’tent-suits’ in order to obviate the need for clothing and housing, asserted that all journeys were actually ‘hallucinations’ resulting from the inability of the human mind to perceive the millions of individual isolated moments which comprise experience, and believed that the night was an accretion of ‘black air’ born of volcanic eruptions and industrial pollution. Multiple erotic encounters between humans and bicycles. Multiple extra-judicial executions, including the hanging of a bicycle (though, not because of its sexual history).

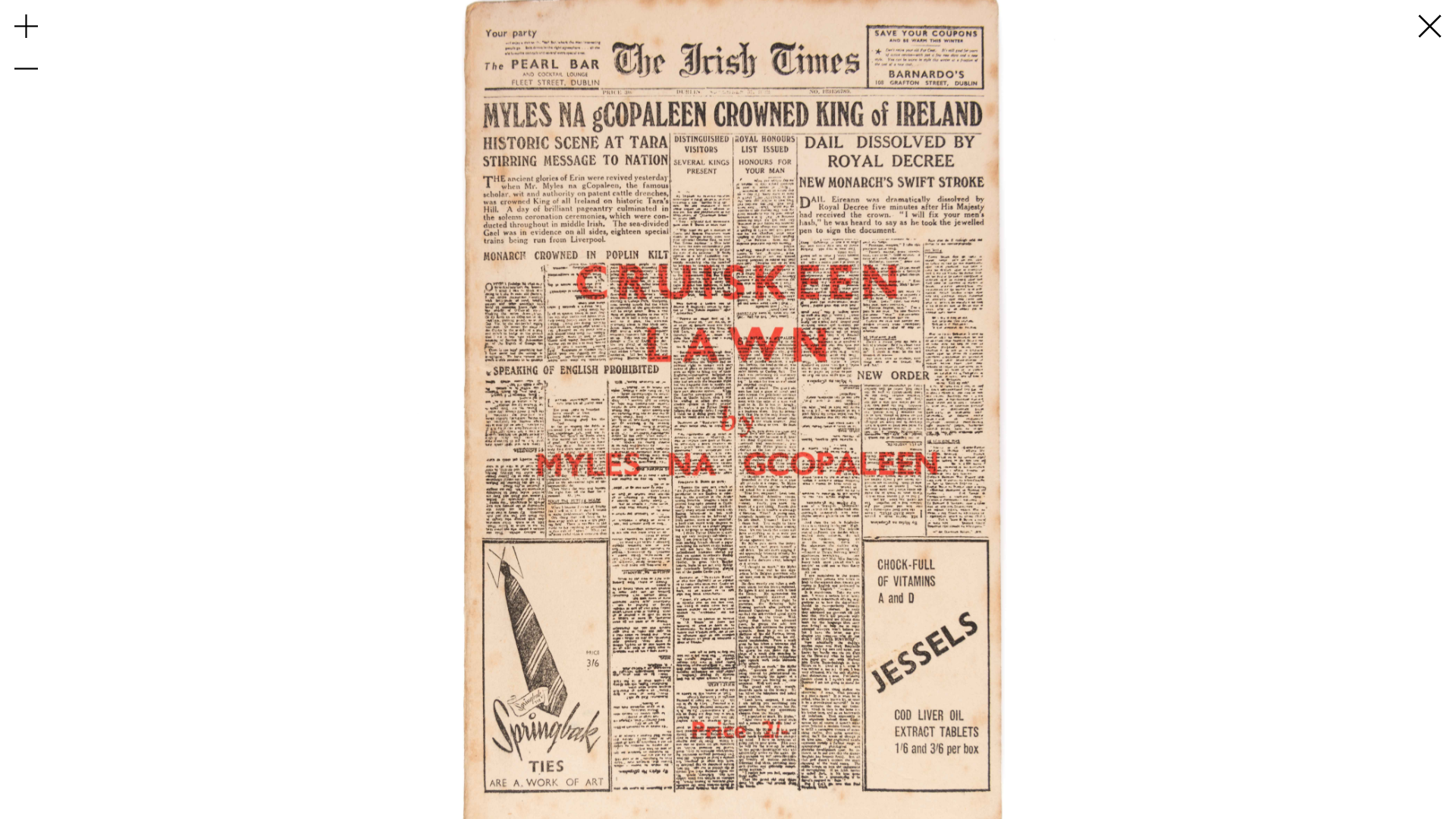

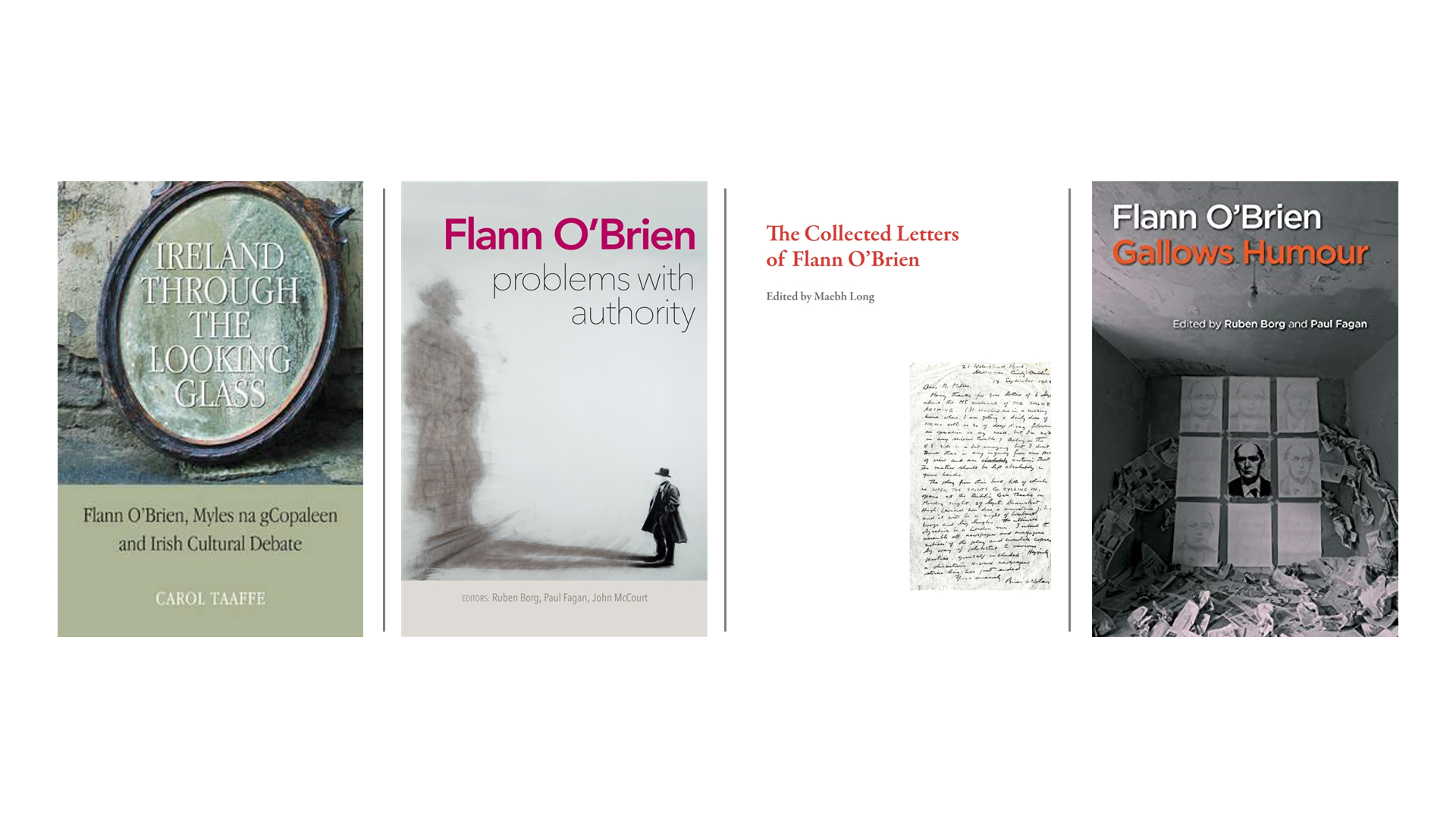

Culminating in a battle between a blind-folded police officer riding an insanity-inducing, Omnium-coated bicycle and an army of one-legged men on a mission to rescue the narrator from the gallows, the novel blends ideas and tropes from science, philosophy, high culture, and popular fiction to hilarious and hallucinatory effect. Most famously, Sergeant Pluck - the first of the novel’s titular policemen - outlines a version of ‘Atomic Theory’ in which the repeated collisions between a bicycle’s seat and the posterior of the person riding it are shown to bring about a transfer of atoms between them that slowly renders the bicycle more ‘human’ and the rider more ‘bicycle’: ‘The gross and net result of it is that people who spent most of their natural lives riding iron bicycles over the rocky roadsteads of this parish get their personalities mixed up with the personalities of their bicycle as a result of the interchanging of the atoms of each of them and you would be surprised at the number of people in these parts who nearly are half people and half bicycles […] And you would be flabbergasted at the number of bicycles that are half-human almost half-man, half-partaking of humanity.’ As a result of this phenomenon, the Sergeant has come to assume that almost all crime is, in some way, a by-product of cycling, and has developed a mode of forensic analysis largely centred around variations on the question ‘Is it about a bicycle?’ Perhaps the most intriguing and subversive by-product of this process is the Sergeant’s own bicycle, which the narrator discovers locked in a cell in the police station: The bicycle itself seemed to have some peculiar quality of shape or personality which gave it distinction and importance far beyond that usually possessed by such machines […] Notwithstanding its cross-bar it seemed ineffably female and fastidious, posing there like a mannequin […] I passed my hand with unintended tenderness - sensuously, indeed - across the saddle […] How desirable her seat was, how charming the invitation of her slim encircling handle-arms, how unaccountably competent and reassuring her pump resting warmly against her rear thigh! With a start I realized that I had been communing with this strange companion and - not only that - conspiring with her. Both of us were afraid of the same Sergeant, both were awaiting the punishments he would bring with him on his return, both were thinking that this was the last chance to escape beyond his reach; and both knew that the hope of each lay in the other, that we would not succeed unless we went together, assisting each other with sympathy and quiet love. Blending an ‘ineffably female’ spirit with conventionally masculine anatomical features (the ‘cross-bar’; the phallic ‘pump’ resting ‘warmly’ and reassuringly against its ’thigh’), the Sergeant’s bicycle not only troubles the boundary between human and machine in a manner that anticipates the modern ‘cyborg’, but strains against the constraints of binary gender and masculine state authority, becoming irresistibly alluring to the narrator in the process. For reasons that are, by now, probably quite apparent, O’Nolan struggled to find a publisher willing to take the risk of issuing The Third Policeman, and the novel wouldn’t find its way into print until 1967, one year after the author’s death. Stung by this rejection and the limited commercial success of his 1941 Irish-language satire, An Béal Bocht [the poor mouth], O’Nolan turned his back on novel-writing, and instead channelled his creative energies into journalism. An absolute menace to the letters pages of the nation’s major newspapers and literary journals, O’Nolan has some right to be considered Ireland’s first and most successful troll, inundating the editors of the Irish Times with a deluge of pseudonymous correspondence so amusing and inventive that, in 1940, they offered him a regular column, Cruiskeen Lawn [the full little jug]. Written in O’Nolan’s haughty and pedantic ‘Myles na gCopaleen’ persona, the column ran virtually uninterruptedly until O’Nolan’s death, and covered everything from the prevalence of cliché in contemporary journalism (‘What is the mean temperature of an altercation? Heated’) to the prevalence of venereal diseases in war-time (‘Veni, VD, Vici’), mixing half-invented gossip with literary pastiche and political satire, often to the detriment of O’Nolan’s Civil Service career. Tempted back to prose fiction by a successful 1960 reissue of At Swim-Two-Birds, O’Nolan completed work on two more novels as ‘Flann O’Brien’ before his death: The Hard Life (1961) and The Dalkey Archive (1964). While neither novel fully succeeds in recapturing the wit and exuberance of his earliest work, both sold relatively well and helped to re-establish O’Nolan’s literary profile. Though he took justifiable pleasure in this long overdue recognition, O’Nolan spent his later years in a state of increasingly poor health, exacerbated by a debilitating alcohol dependence and a variety of accidents and mishaps, and entered hospital for the last time in early 1966, where he died while suffering from cancer of the pharynx. In the years following his death, O’Nolan’s reputation as a major figure in the history of Irish literature, science fiction, and experimental writing has been consolidated through a growing body of scholarship devoted to his writing. However, though O’Nolan himself wrote for stage, radio, and TV, his work has proven notoriously difficult to adapt, particularly for the screen. And this, I think, is where gaming comes in. No medium is better equipped to render the radical shifts in perspective, the complex fusion of genres, and the probing questions about free-will and determinism that characterise O’Nolan’s work than videogames. It is easy to imagine O’Nolan chuckling at the Portal franchise’s blackly comic satire of the scientific method and the sadism its apparent rationalism often serves to mask, or to picture him smiling appreciatively at the ways in which a game like Undertale affectionately remixes the aesthetic and conventions of an 8-bit adventure game to ask probing questions about what is at stake in the act of ‘play’ itself. It is not hard to imagine O’Nolan becoming downright litigious when confronted with The Stanley Parable, which, with its circular and self-undermining structure, multiple-choice beginnings and endings, and meta-narrative tug-of-war between the guiding hand of the narrator and the free-will of the player, is basically already a pitch-perfect adaptation of At Swim-Two-Birds. At a moment in which developers are straining against the limits of the form and interrogating the codes and conventions of gaming like never before, the time is undoubtedly right for a game which truly makes us ask ‘Is it about a bicycle?’ Resources The Parish Review, the official scholarly journal of the International Flann O’Brien Society, is free to access via the Open Library of the Humanities and offers a rich set of resources for those interested in O’Nolan’s life and work. For an engaging and accessible discussion of the philosophy of The Third Policeman, check out this podcast from the London School of Economics’ Forum for Philosophy. For a more in-depth exploration of O’Nolan’s writing and approach to questions of sex, death, and embodiment, check out Flann O’Brien: Gallows Humour (Cork University Press, 2020), where I can be found discussing O’Nolan’s approach to the politics of sexual health in mid-twentieth-century Ireland.